Robert writes:

How do you build the “wow” into your police organization to meet or exceed citizen expectations? How do sergeants add a “wow” to their patrol team or an investigations unit? “Wow” is not a new program acronym; it is a philosophy of wowing citizens whenever possible. It is about combining empathy into living an agency’s vision, mission and values. How do you take those fancy agency visions that adorn police lobbies and hallways across the country and turn them into real-world service delivery? Here is a process that any agency can use as a template to help focus on community successes.

How do the police view the police?

First, how does the public see the police, and how do we police see ourselves? Warriors, protectors, guardians, enforcers or some combination thereof? Survey data shows that 62% of police officers view their primary role as a combination of being a protector and an enforcer. Yet 52% of the public view the police in the same way.

Survey data shows that 31% of police officers believe their primary role is to serve as a protector. Only 16% of citizens view their local police as protectors.

An even larger disparity between police–public views emerges over the enforcement role of police. Only 8% of officers say they see themselves as enforcers — the long arm of the law — yet fully three times the share of the public (29%) see their local police that way.

This disparity over how the public views police and how officers see their role is partially explained by race. African Americans are significantly more likely than whites to see their local police as mainly enforcers (39% versus 26%) and less likely to see officers as both protectors and enforcers (43% versus 57%).

Overall, 46% of Hispanic adults see police in their community as both enforcers and protectors, while 33% view them as enforcers and 14% as protectors. Among Hispanic officers, about two-thirds (65%) see their role to be both protectors and enforcers, while 7% say they are enforcers and 28% consider themselves to be protectors.

Is the message and delivery of police services mirroring our objective? Can we say that uniformly our profession has a marketing campaign? In an era of the 24-hour news cycle and social media, law enforcement must also embrace marketing as a core agency function along with service delivery.

What good policing looks like

The American Bar Association (ABA) identifies good policing as having four key factors: professionalism, accountability, transparency and self-monitoring.

Professional. Good policing serves the public effectively and continually seeks and adopts proven best practices such as law enforcement accreditation. Prior to 2020, there were no laws or regulations mandating accreditation in law enforcement. Currently, it is estimated that only 3% of agencies nationwide have achieved accredited status. Due to a number of high-profile events and public calls for police reform, Connecticut, Oregon and Florida have passed legislation requiring agencies to obtain accreditation.

Accountable. It is not just about holding officers accountable to state-of-the-art policies. Policy generation and accountability is a time-consuming and never-ending commitment to continuous improvement. It is about training that puts policies into action in a classroom, using simulators and hands-on practice. Independent citizen oversight boards and agencies have emerged when proactive accountability has become muddled in bureaucracies that fail citizens. Early intervention systems (EIS), solid evaluation tools and tracking work performance can all help motivate employees to grow instead of allowing negative behaviors to spiral out of control.

Transparent. Transparent police agencies embrace the positive side of the internet. Information-packed websites that open the doors to police programing, annual reports, crime data, division operations and agency points of contact must be invested in. Just as important is the proactive use of text and email alerts, Twitter, Facebook and nextdoor.com to name a few. There are costs associated with each of these steps; they can no longer be cut or unfunded because there is no budget for them. There will not be a budget if an ostrich syndrome envelopes a police agency.

Self-monitoring. Good policing does not just look out into the community; it requires connecting with citizens at all levels in an agency. Self-monitoring must also be introspective. Regular self-monitoring, self-reviewing and lessons-learned procedures should be put into practice — especially after use-of-force incidents and shootings.

Strengthening citizen relations

In August, the Center for Public Safety Management (CPSM) and the International Association of Chiefs of Police hosted their first joint training program for local government managers and their chiefs of police. The seven manager–chief teams identified eight practices to improve police–community relations.

- Lasting collaborative relationships between local police and the public are essential. Problem-solving partnerships between the police chief and city manager are critical to success.

- Clear, comprehensive policies addressing scenarios such as use of force, mass demonstrations, consent before searches, gender identification, performance measures and collection of data need to be in place and must be reflective of the communities served.

- It is important to be open to new technology, but we must think through policies of use with transparency, accountability and privacy in mind.

- Reinforce community policing with an emphasis on protection, procedural justice and dignity for all. Foster cooperation, community engagement and positive nonenforcement activities.

- Avoid tactics that stigmatize youth. Support youth leadership and life-skills training, and provide incentives for officers to involve themselves as role models for youth.

- Avoid practices that lead to disparate impacts on segments of the community. Prohibit racial profiling, sexual harassment or misconduct, and quotas or other incentives for arrests, citations or tickets generating revenue.

- Emphasize de-escalation and alternatives to arrest, interagency collaboration, shared services and regional training.

- Embrace training for recognizing and avoiding implicit bias, guardian/protector versus warrior mindset, dealing with those who have mental health disabilities, and officer safety and wellness.

Enforcement

A study published in the journal Science Advances provides the first evidence that visible efforts by authorities to treat people fairly, regardless of whether the interaction results in punishment — or even when enforcement decisions are based on a mistake — make people intrinsically more motivated to cooperate and comply with the law.

“Imagine being pulled over for coasting through a stop sign when you’re certain that you stopped,” said Gregory Huber, the Forst Family professor of political science in the faculty of arts and sciences at Yale University. “Our findings suggest that if the police officer explains their decision and behaves in a visibly fair manner, then people are more likely to perceive the officer’s actions as legitimate even if the officer is mistaken.”

Where is the “wow”?

Management must lead the “wow” with a solid mission, vision and guiding principles in place. Those must be more than words on paper. They should be part of the daily decision-making tree throughout the organization. That requires educating all employees and then revisiting that discussion on a regular basis. Fortune 500 companies invest time, money and action in culture building. Do we?

This “wow” message needs to be part of in-service training, meetings and briefings.

The day-to-day “wow” has to come from the sergeant guiding his/her team, from detectives who care, the officer on patrol and dispatchers who have empathy and from a team that leaves citizens exiting an encounter, traffic stop or filing a crime report with a feeling that this officer and that agency gave them more than they expected. Much of the time, police legitimacy begins with acting, thinking and talking like a concerned human being.

Doesn’t this involve selling yourself as a professional who can be trusted, doing your job to the best of your ability, which generates public confidence, and having empathy for people? It will, and that’s the beginning of the “wow.”

- Originally published by Robert Spinks in June 2023 in American Police Beat publication, and apbweb.com.

Robert Spinks started his career in 1981 with the Eugene Police Department in Oregon and later served at the Port of Seattle Police Department in Washington. He has been the chief of police in Sedro-Woolley, Washington; Milton-Freewater, Oregon; Sequim, Washington; McNeese State University; and is currently the chief in Parsons, Kansas. He is an instructor and adjunct faculty at the University of Arizona Global Campus and Labette Community College. Community policing information can be downloaded at parsonspd.com.

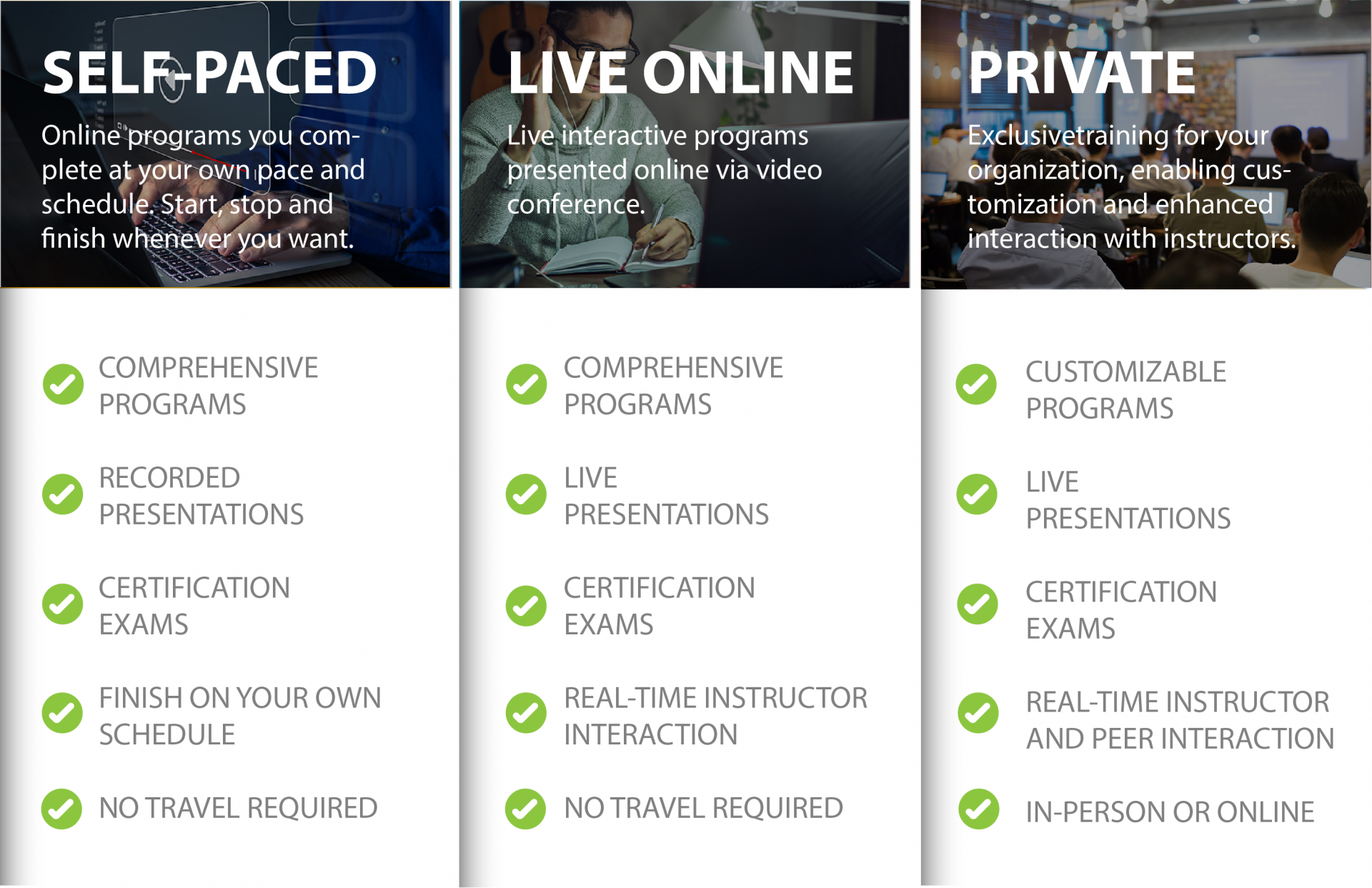

SPRING 2024 COURSES AVAILABLE!

Visit our website to view the live virtual spring course schedule,

program descriptions and register.

EARLY BIRD DISCOUNT!

Seminar registrations received by February 18th will receive a 20%

discount with code SPRING24EARLY